Tuesday, September 10, 2013

Festina Lente: Re-imagining UT Austin

Over the next semester, I am going to be writing opinion columns about the landscape of higher education in Texas and the consequences for the UT Austin campus. This is the first, introductory column, where I describe the project (and reference the Roman emperor Augustus!) I'll be visiting classes around campus, talking to instructors, and getting feedback from students in an effort to try to figure out what works and what doesn't, in both online and onsite classrooms. I'm very excited about this opportunity, not least because it will give me an excuse to learn a lot more about what is happening in campuses around the UT Austin campus.

Saturday, August 31, 2013

The Real Magic Formula: Formative Assessment

Earlier this week, Dr. James Pennebaker and Dr. Sam Gosling, two UT Austin professors in the Department of Psychology, launched a live-streaming online course that they are calling a SMOC (Synchronous Massive Online Course). The nomenclature is a clear riff on the MOOC (Massive Open Online Course); but the SMOC differs in a couple of ways. First, it is not open. In fact, it costs $550 (still, less expensive than a classroom-based course at UT Austin). It is massive by most standards, in that it enrolls about 1000 students (they are hoping to increase that number to 10,000 eventually)--but not the multiple tens or even hundreds of thousands who register for MOOCs. Finally, as they highlight, it is live rather than pre-recorded. Students are required to sign in at the start of class to take short "benchmark" quizzes. Since there is no participation grade, it does seem that students can opt to sign out once they have finished the quiz and watch the archived recording of the class at their leisure to prepare for the next benchmark quiz. The course does include moments for live chats and polls, in an effort to engage students during the live broadcast. Still, as someone who teaches a similar audience, I wonder how many will, in fact, engage regularly during the live broadcasts, especially as the semester goes on.

Earlier this week, Dr. James Pennebaker and Dr. Sam Gosling, two UT Austin professors in the Department of Psychology, launched a live-streaming online course that they are calling a SMOC (Synchronous Massive Online Course). The nomenclature is a clear riff on the MOOC (Massive Open Online Course); but the SMOC differs in a couple of ways. First, it is not open. In fact, it costs $550 (still, less expensive than a classroom-based course at UT Austin). It is massive by most standards, in that it enrolls about 1000 students (they are hoping to increase that number to 10,000 eventually)--but not the multiple tens or even hundreds of thousands who register for MOOCs. Finally, as they highlight, it is live rather than pre-recorded. Students are required to sign in at the start of class to take short "benchmark" quizzes. Since there is no participation grade, it does seem that students can opt to sign out once they have finished the quiz and watch the archived recording of the class at their leisure to prepare for the next benchmark quiz. The course does include moments for live chats and polls, in an effort to engage students during the live broadcast. Still, as someone who teaches a similar audience, I wonder how many will, in fact, engage regularly during the live broadcasts, especially as the semester goes on.The start of the course has been accompanied by quite a lot of publicity: an op-ed in the Houston Chronicle; an article in Inside Higher Ed; several press announcements from UT Austin; a television appearance on Good Day Austin; The Daily Texan (and here); and, now, articles in the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times. There is also a Twitter feed for the class: @PsyHorns. The press coverage emphasizes the innovation of the model, in particular, the claim that the live streaming broadcast as well as the delivery platform (an in-house product developed by UT Austin and aptly named Tower) facilitate connectivity and active engagement in a way that the MOOCs and other large enrollment online classes have not. This is certainly a noble aspiration, but a lot depends on the students. This is especially true since no part of the final grade is connected to engagement in the live broadcast. I do hope that, at the end of the semester, Pennebaker and Gosling will release at least preliminary data about student engagement: how many logged off immediately after the quiz? How many engaged in one poll or pod discussion? all of them? Are there connections between final grades and participation in the live broadcast versus reviewing the archived broadcast? These are important questions for faculty who are designing their own version of an online course.

I am grateful that I've been given the chance to audit this course. Mainly, I am interested in experiencing Tower from the student perspective, as I work through the design of Rome Online. I am especially interested in the question of connectivity--how to facilitate connections to me but especially between students in a virtual classroom that may well contain hundreds of students. I am looking forward to seeing how Pennebaker and Gosling make use of the Tower platform; and how they manage the strengths and weaknesses of a synchronous broadcast to a large audience (though, at least in the current iteration, not any larger than they've taught in previous years in various configurations: c. 1000 students).

One tool I am going to be watching closely is the benchmark quiz. The Tower platform has a very nice quiz tool that I am hoping to use in my own online course. I am eager to experience it from the student point of view. As I discovered in my own rather large (but only 400 students) course last spring, a key element for improving student learning is structure--and especially, frequent quizzes. This point is made clearly in the WSJ article: "Recently, they moved one class of students online and gave them multiple-choice tests that delivered instant feedback. That group performed better than their offline class—and the online students' grades even improved in their other classes. The professors hypothesize that it is because the regular quizzes helped the students acquire better study habits."

There's an important point here: improved student performance in a course (whether the Intro to Psychology or any other large enrollment course) is not a consequence of any technological bells and whistles but rather, an instructional design decision--to overhaul the class assessment and put much more emphasis (and weight) on quizzes rather than large stakes midterms. This was the case for Intro to Psych; it was also true in my Intro to Ancient Rome class. In large classes, regardless of mode of instruction, students require a lot of structure. In my Rome class, I continued to give midterms, so that I had ways to compare the different cohorts. I suspect that, if midterms were still offered in the Intro to Psych class, they'd find that the benchmark quiz cohort performed better than the midterms only cohort. There's a pretty basic reason for this improved performance: quizzes require students to study as they go rather than try to cram a month's worth of learning into a few days.

One thing that would be interesting to know is whether, in a "benchmark quiz" cohort, there's any correlation between grades on quizzes and engagement during the live broadcast. If there is, that's a good argument for the high cost of producing a live streaming broadcast. If there's not, that tells us that the value is in the formative assessment rather than the mode of delivery. It's these sorts of questions that are important to test as we move forward with offering online versions of our campus-based courses.

Friday, August 30, 2013

Rome Online Course: The Challenge of Connecting Students in an Online Environment

The building that houses my campus office also includes several classrooms. Students like to congregate in the halls, waiting for the previous class to finish. My first office was directly across from a classroom. It was nearly impossible to get any real work done at work between 9 am-3 pm, between the chattering students and the sounds from the classroom. At one point, our office manager put signs up, to limited effect, to remind students not to talk.

These days, it's pretty quiet in the halls, especially in the early days of the new semester. Students are staring at the phones, not making conversation with those around them. Two friends might be chatting, but otherwise, silence and intense focus on their smart phone. This scene repeated itself as I arrived at the auditorium where I teach my Rome class. As the students made their way into the room and found seats, I was heartened to hear them talking to one another--not everyone, but enough that it was pretty noisy. There's something deeply interesting about the fact that, these days, we aren't worried about students talking to one another too much but, rather, too little.

In large enrollment courses, students will have a much easier time engaging in the course--and even showing up--if they feel a connection to their classmates. Back in the olden days (i.e. when I was in college in the 90s), going to class was a social experience. It was where we connected with friends, made plans for after class, and shared experiences that we then rehashed, parsed, and joked about--and continue to, even all these years later. We walked around campus in packs, frequently stopping to chat with friends we encountered along the way. Only the most anti-social of us walked around with a walkman and ear phones. But times and social mores change. Now, as instructors, we often have to actively work to encourage our students to see the classroom as a place for experiencing and benefiting from the social aspects of learning. This is especially true on a very large campus like UT Austin, and in the very large courses on these campuses. The default mode for students, unless they already know some of their classmates, is to isolate, be silent and passive.

By incorporating a student response system (i>clickers), peer instruction, class discussion and a discussion board; as well as encouraging group work on a wide range of other activities, I feel like I have done about as well as I can to push students to get to know their classmates, to take advantage of the power of distributed learning. Some choose not to to engage, and I let them be. But I make sure that they are deliberately choosing to opt out of an established norm rather than following the norm. Certainly, it's possible to take my class without ever engaging much with classmates--or even showing up to class for more than the weekly quizzes. But this means sitting along, watching videotapes of lectures, not sharing in the communal laughter. Most students quickly realize that it's more fun to be there.

I am coming to see that a big--if not the biggest--challenge in developing an online version of my Rome class is finding a way for the students to feel connected to one another. Sure, it helps a lot if they feel connected to the course instructor; but the real focus of the course design needs to be on finding ways to encourage the to connect to one another, and to facilitate that connection at the very start of the course. Watching the "Doc on the Laptop" alone is isolating. For anyone whose normative educational experience involves sitting in the same room as the instructor and their classmates, it's a constant reminder of distance, inaccessibility. There is some thought that synchronous live streaming lectures help to lessen this perception of distance. I'm not sure. For many students, it might well heighten it.

The central challenge is overcoming the entropy of the massive (whether 400 or 10, 000 or 40,000). In a large course, I think, it is realizing that the primal connection is that which exists between peers rather than student to instructor. Or, to put it a slightly different way, it's recognizing that the instructor is just another person. It seems that, at least early on, a key element of any course platform has to be a well-conceived chat function, that can group students but also let each student know with whom they've been chatting and have a way for them to Direct Message one another. In a synchronous class, perhaps it makes sense to group students before the class starts and ask them to introduce themselves to one another. In an asychronous class, it probably makes sense to group students into discussion groups and have them respond to prompts, with an instructor or TA helping to guide the discussion.

I suspect it might also be easier for students to take advantage of the synchronous elements of a class if, first, they have done some form of asynchronous conversation with their peers. That is to say, given the expense of producing a synchronous course, it probably makes sense to use that element sparingly and only when it is going to produce a lot of "bang for the buck." From a pedagogical perspective, it's likely to be a lot more effective once the class is underway, once students have already had a chance to engage with one another (and the instructor) in various asynchronous formats. For instance, I can imagine having steady groups for each unit of the Rome course. And at the end of each unit, doing a synchronous broadcast that asked students to engage in polls, chat with one another, etc. And then shuffling the groups for the next unit, with some people staying together.

The key, though, is a very sophisticated chat tool. Discussion boards are useful, but as the size increases, the boards are populated by a lot of individuals posting their individual thoughts without much attention to engaging with the thoughts of their classmates. This seems inevitable, and the only real solution is to break large classes into smaller groups. This is also true for chat groups during a synchronous broadcast--any more than 4 or 5 people and it is a bunch of people typing, saying the same thing, not interacting with one another in any real way. The time lag only exacerbates the problem.

These days, it's pretty quiet in the halls, especially in the early days of the new semester. Students are staring at the phones, not making conversation with those around them. Two friends might be chatting, but otherwise, silence and intense focus on their smart phone. This scene repeated itself as I arrived at the auditorium where I teach my Rome class. As the students made their way into the room and found seats, I was heartened to hear them talking to one another--not everyone, but enough that it was pretty noisy. There's something deeply interesting about the fact that, these days, we aren't worried about students talking to one another too much but, rather, too little.

In large enrollment courses, students will have a much easier time engaging in the course--and even showing up--if they feel a connection to their classmates. Back in the olden days (i.e. when I was in college in the 90s), going to class was a social experience. It was where we connected with friends, made plans for after class, and shared experiences that we then rehashed, parsed, and joked about--and continue to, even all these years later. We walked around campus in packs, frequently stopping to chat with friends we encountered along the way. Only the most anti-social of us walked around with a walkman and ear phones. But times and social mores change. Now, as instructors, we often have to actively work to encourage our students to see the classroom as a place for experiencing and benefiting from the social aspects of learning. This is especially true on a very large campus like UT Austin, and in the very large courses on these campuses. The default mode for students, unless they already know some of their classmates, is to isolate, be silent and passive.

By incorporating a student response system (i>clickers), peer instruction, class discussion and a discussion board; as well as encouraging group work on a wide range of other activities, I feel like I have done about as well as I can to push students to get to know their classmates, to take advantage of the power of distributed learning. Some choose not to to engage, and I let them be. But I make sure that they are deliberately choosing to opt out of an established norm rather than following the norm. Certainly, it's possible to take my class without ever engaging much with classmates--or even showing up to class for more than the weekly quizzes. But this means sitting along, watching videotapes of lectures, not sharing in the communal laughter. Most students quickly realize that it's more fun to be there.

I am coming to see that a big--if not the biggest--challenge in developing an online version of my Rome class is finding a way for the students to feel connected to one another. Sure, it helps a lot if they feel connected to the course instructor; but the real focus of the course design needs to be on finding ways to encourage the to connect to one another, and to facilitate that connection at the very start of the course. Watching the "Doc on the Laptop" alone is isolating. For anyone whose normative educational experience involves sitting in the same room as the instructor and their classmates, it's a constant reminder of distance, inaccessibility. There is some thought that synchronous live streaming lectures help to lessen this perception of distance. I'm not sure. For many students, it might well heighten it.

The central challenge is overcoming the entropy of the massive (whether 400 or 10, 000 or 40,000). In a large course, I think, it is realizing that the primal connection is that which exists between peers rather than student to instructor. Or, to put it a slightly different way, it's recognizing that the instructor is just another person. It seems that, at least early on, a key element of any course platform has to be a well-conceived chat function, that can group students but also let each student know with whom they've been chatting and have a way for them to Direct Message one another. In a synchronous class, perhaps it makes sense to group students before the class starts and ask them to introduce themselves to one another. In an asychronous class, it probably makes sense to group students into discussion groups and have them respond to prompts, with an instructor or TA helping to guide the discussion.

I suspect it might also be easier for students to take advantage of the synchronous elements of a class if, first, they have done some form of asynchronous conversation with their peers. That is to say, given the expense of producing a synchronous course, it probably makes sense to use that element sparingly and only when it is going to produce a lot of "bang for the buck." From a pedagogical perspective, it's likely to be a lot more effective once the class is underway, once students have already had a chance to engage with one another (and the instructor) in various asynchronous formats. For instance, I can imagine having steady groups for each unit of the Rome course. And at the end of each unit, doing a synchronous broadcast that asked students to engage in polls, chat with one another, etc. And then shuffling the groups for the next unit, with some people staying together.

The key, though, is a very sophisticated chat tool. Discussion boards are useful, but as the size increases, the boards are populated by a lot of individuals posting their individual thoughts without much attention to engaging with the thoughts of their classmates. This seems inevitable, and the only real solution is to break large classes into smaller groups. This is also true for chat groups during a synchronous broadcast--any more than 4 or 5 people and it is a bunch of people typing, saying the same thing, not interacting with one another in any real way. The time lag only exacerbates the problem.

Thursday, August 29, 2013

It's Magic!

|

| Sebastian Thrun, Founder of Udacity: "The thing I'm insanely proud of right now is I think we've found the magic formula." |

Despite nearly twenty years of teaching experience, first as a grad student and then a professor, I still get the jitters before the first class meeting. This is especially true when I teach my ginormous Introduction to Ancient Rome class: 400 students and a range of previous experiences with learning history and reasons for taking the course. From demographic surveys, we know that most of them are there to fulfill a core curriculum requirement; but, for whatever individual reason, they've chosen to take this class instead of some other class that fulfills that requirement. I love walking in on the first day of class and seeing that so many students are going to be learning about ancient Roman history and culture. They are going to be learning about the evidence historians use and how we evaluate it. They are also going to be learning that you can't blindly trust everything you read or see. You have to think about the larger historical and cultural context that produced that text or monument.

The first few weeks are all about orienting the students to the many moving pieces of the course. Most especially, they are about setting expectations for the level of active engagement with the content that I am going to expect from them inside and outside of class. This requires a tremendous amount of thought, organization and hard work from me and my teaching team (four graduate student TAs). Going into this fall semester, I feel pretty optimistic that my structure for the class as well as the "protocol" in place will, on the whole, work to motivate students to make good choices (e.g. stay on top of the course material; attend class meetings). If they make good choices, chances are in their favor that they will learn more and better; and earn a higher grade than they would have if they were in my traditional lecture version of the course.

Still, at the end of the day, everything depends on the students. I can set up a course that motivates and rewards good learning behaviors; but I can't make them learn. All to say, there is no "magic formula" in higher education. Or, perhaps, better said: the real magic formula is investing a whole lot more money in public education, so that we are not teaching 400 students at a time. The "magic formula" is a strong and positive relationship between instructor and student. When we are talking about teaching hundreds or thousands of students at a time, however, we can do our best to set them up for success; but learning is ultimately their responsibility.

As well, in actual college classrooms, we don't have the luxury of improving our learning outcomes by changing our student demographic. There's nothing novel or magical here. Highly selective colleges and universities learned this trick a long time ago: if you want to boast about the success of your graduates, only admit the very best and most prepared students. It's hard work--and risky--to admit students who are less well-prepared, who need a lot of guidance from experts. As university professors, we work with what we have. I am lucky, in that the make-up of my students doesn't change a whole lot from year to year. Still, one of the challenges of the large class is finding ways to identify and provide help for the students who are struggling. It's also knowing when and how to intervene.

I wish there was a magic formula for this, but there's not, at least not yet. Maybe someday a magic algorithm will be able to predict early in the semester that a student is going to struggle. In the meantime, my TAs and I have to use the many combined years of experience we have to work with the range of students that we have. We do a pretty good job, but it's hands on, a lot of time and effort from us as well as the students. Then again, I've not yet tried to wave my magic wand and cast a spell...

Monday, August 26, 2013

Rome Online Course*: Re-imagining my Presence (and Planning for my Absence)

As I begin to think seriously about the design for the online version

of my Intro to Ancient Rome class, which we are planning to launch on

Canvas in Summer 2014, I find myself thinking a lot about my own role.

The MOOC mania gave rise to what Jonathan Rhees has aptly termed a class

of Super Professors--professors who were suddenly performing in front

of audiences in the tens of thousands instead of the usual few hundred.

Oftentimes, these mostly (though not always) very senior faculty were

well-known for their academic achievements and, because of the nature of

the MOOC Incs, taught at very prestigious institutions. They were

front and center of their courses, as much because the main pedagogical

format was content deliver via pre-recorded lecture. That is to say, a

student wasn't just learning about the ethics of justice; he was

learning Michael Sandel's version of that content. In courses like

coding, calculus, or even physics, the outsized presence of the

instructor was lessened by the nature of the content; but especially in

liberal arts topics, the course could be as much about the instructor as

the content. Of course, this is also true for traditional lecture

courses taught in a campus classroom.

As a sometime student of MOOCs and other types of online courses, it seems to me that this model, this emphasis on the instructor, gets it exactly backwards. While it makes some kind of sense for an instructor to rely on the personal charisma generated by their presence in a face-to-face class or even a blended class, it makes little sense to do it in a purely online class. The absent-presence of the instructor speaking at the student through a computer is a constant reminder of the distance that separates instructor from student. It is a constant reminder that, however accessible the professor seems, s/he is ultimately inaccessible. People will argue that this is no different than the experience of sitting in a 500-student classroom, but I'm not so sure. The more I teach a very large (400 student) class, the more convinced I am that a good design for an online course will move away from being an imperfect substitute for an interactive lecture course; and move towards something entirely different.

My own sense is that this different thing needs to have a place for the instructor to construct and practice his/her authority; but that, in some real sense, it's important to concede the point that no amount of fancy computer mediation, not even live streaming, can replicate the experience of being in a classroom with us. I;m not sure I'd have believed this until I taught a pure flipped class last fall. The students watched all the lectures outside of class; and class time was devoted to practicing the content. About 30% thought this was great. Those are the ones who would be a natural audience for an online class, I think. But the other 70% were somewhere between hated it and "meh". Those are the students who need us to take seriously the differences of online vs f2f course delivery. There is already a rich body of research on this topic, and those of us who are or are planning to teach online courses need to know it and take account of it in our course design.

The other important thing that our course design needs to take account of is the possibility that we might not be the instructor. In my own case, for instance, I plan to teach a few iterations of the course but then, most likely, will hand it off to others to teach most of the time. Planning for this is extremely important and, again, suggests that less reliance on pre-recorded lectures from a single instructor is the way to go. As I begin to make concrete plans, I am thinking hard about a. how to deliver content in ways other than lecture; and b. how to involve a number of voices in the content delivery, so that it doesn't seem to students like I am somehow "MIA" if I am not the instructor. Having students construct and master content through modules and reserving lecture only for very difficult or amusing topics is one clear answer. I am also thinking about how to build into the design places for other instructors to incorporate their own material. I am thinking about how to balance synchronous and asychronous elements of the course.

Part of the sustainability of my course depends on design decisions made at the start; and it depends on the recognition that student learning nearly always requires some sort of relationship between instructor and student--a relationship that is impeded if someone else is always appearing on the screen as the sage on the stage. For this same reason, I am extremely skeptical that licensed MOOCs will be all that effective in the long run for subjects like mine. Students don't put nearly as much weight on an instructor's professorial rank and status as most faculty and administrators do. Most of them don't know the difference between a lecturer and a full professor, nor do they care. They care that their course is taught in a way that facilitates their learning and, hopefully, provides an enjoyable experience. Part of this experience is the connection they forge with the course instructor, whether during office hours on campus or via email and discussion boards and Google Hangouts in an online course. It is essential than any online course design provide space for a new instructor to put their own imprimatur on a course, establish their authority, without the constant distraction of an absent, inaccessible sage on the stage.

*ROC (Rome Online Course). I am planning to write regularly about my plans for developing my Intro to Rome class for an online audience, including the particular challenges of planning from the start for multi-modal delivery; and for handing the instruction over to others on a regular basis.

As a sometime student of MOOCs and other types of online courses, it seems to me that this model, this emphasis on the instructor, gets it exactly backwards. While it makes some kind of sense for an instructor to rely on the personal charisma generated by their presence in a face-to-face class or even a blended class, it makes little sense to do it in a purely online class. The absent-presence of the instructor speaking at the student through a computer is a constant reminder of the distance that separates instructor from student. It is a constant reminder that, however accessible the professor seems, s/he is ultimately inaccessible. People will argue that this is no different than the experience of sitting in a 500-student classroom, but I'm not so sure. The more I teach a very large (400 student) class, the more convinced I am that a good design for an online course will move away from being an imperfect substitute for an interactive lecture course; and move towards something entirely different.

My own sense is that this different thing needs to have a place for the instructor to construct and practice his/her authority; but that, in some real sense, it's important to concede the point that no amount of fancy computer mediation, not even live streaming, can replicate the experience of being in a classroom with us. I;m not sure I'd have believed this until I taught a pure flipped class last fall. The students watched all the lectures outside of class; and class time was devoted to practicing the content. About 30% thought this was great. Those are the ones who would be a natural audience for an online class, I think. But the other 70% were somewhere between hated it and "meh". Those are the students who need us to take seriously the differences of online vs f2f course delivery. There is already a rich body of research on this topic, and those of us who are or are planning to teach online courses need to know it and take account of it in our course design.

The other important thing that our course design needs to take account of is the possibility that we might not be the instructor. In my own case, for instance, I plan to teach a few iterations of the course but then, most likely, will hand it off to others to teach most of the time. Planning for this is extremely important and, again, suggests that less reliance on pre-recorded lectures from a single instructor is the way to go. As I begin to make concrete plans, I am thinking hard about a. how to deliver content in ways other than lecture; and b. how to involve a number of voices in the content delivery, so that it doesn't seem to students like I am somehow "MIA" if I am not the instructor. Having students construct and master content through modules and reserving lecture only for very difficult or amusing topics is one clear answer. I am also thinking about how to build into the design places for other instructors to incorporate their own material. I am thinking about how to balance synchronous and asychronous elements of the course.

Part of the sustainability of my course depends on design decisions made at the start; and it depends on the recognition that student learning nearly always requires some sort of relationship between instructor and student--a relationship that is impeded if someone else is always appearing on the screen as the sage on the stage. For this same reason, I am extremely skeptical that licensed MOOCs will be all that effective in the long run for subjects like mine. Students don't put nearly as much weight on an instructor's professorial rank and status as most faculty and administrators do. Most of them don't know the difference between a lecturer and a full professor, nor do they care. They care that their course is taught in a way that facilitates their learning and, hopefully, provides an enjoyable experience. Part of this experience is the connection they forge with the course instructor, whether during office hours on campus or via email and discussion boards and Google Hangouts in an online course. It is essential than any online course design provide space for a new instructor to put their own imprimatur on a course, establish their authority, without the constant distraction of an absent, inaccessible sage on the stage.

*ROC (Rome Online Course). I am planning to write regularly about my plans for developing my Intro to Rome class for an online audience, including the particular challenges of planning from the start for multi-modal delivery; and for handing the instruction over to others on a regular basis.

Sunday, August 25, 2013

MOOCs, SMOCs, Super Professors and Online Course Design

This weekend, two of my colleagues at the University of Texas, Austin wrote about their Introduction to Psychology SMOC (Synchronous Massive Online Course) in the Houston Chronicle. For $550, anyone, anywhere can register for their course and earn credit from UT Austin. The selling point of the SMOC over the MOOC is personalization, both via an "unparalleled teaching platform" designed in-house (known as Tower); and through peer discussion led by a peer mentor (a student who has already taken the course): "While the thousands of students watch our live lectures, they will each

be in small "pods" with other students to discuss the class as it

unfolds. Each pod will have a mentor who took the class last year." As in most MOOCs, the instructors will lecture, but live rather than pre-recorded. Unlike most MOOCs (though more are experimenting on this front), the class session will involve discussion amongst the "pods" of students and, presumably, some sort of computer-mediated "conversation" with the instructors. What this all looks like in practice, and how well the technology holds up at scale, remains to be seen. This much is clear: the course design of this SMOC aims to be more interactive than at least the stereotypical MOOC; but it retains essentially the same role for the instructors--and, more importantly, keeps them fairly removed from the individual students. The may be "world famous instructors" but nearly every student in the course will experience them in the same way they experience a TV performer--at a substantial distance.

In reality, there's not much difference between this SMOC and a MOOC like Al Filreis's ModPo from Coursera, which films live discussions, takes questions, etc. Indeed, the main difference is that this SMOC is not "open". Access is limited to those who pay the $550 registration fee. The SMOC offers credit based on student performance on "benchmark quizzes" before each class whereas the MOOC offers non-credit "certificates of achievement" based on student performance on quizzes and peer-graded assignments. A point that the instructors emphasize in their advertising for the course is the absence of large stakes assessments and the associated stress. [Sidenote: I am a big fan of low-stakes assessments, but I'd like to see the midterms retained in the initial stages of developing this delivery model, as much so that it is clear to possible critics of the method that the students are learning as much and as well as students in other versions of the course. This seems especially important at this point since, despite best efforts, it's still very difficult to control for cheating on these quizzes. Students tend to be very good at finding ways around our best obstacles.]

In reality, there's not much difference between this SMOC and a MOOC like Al Filreis's ModPo from Coursera, which films live discussions, takes questions, etc. Indeed, the main difference is that this SMOC is not "open". Access is limited to those who pay the $550 registration fee. The SMOC offers credit based on student performance on "benchmark quizzes" before each class whereas the MOOC offers non-credit "certificates of achievement" based on student performance on quizzes and peer-graded assignments. A point that the instructors emphasize in their advertising for the course is the absence of large stakes assessments and the associated stress. [Sidenote: I am a big fan of low-stakes assessments, but I'd like to see the midterms retained in the initial stages of developing this delivery model, as much so that it is clear to possible critics of the method that the students are learning as much and as well as students in other versions of the course. This seems especially important at this point since, despite best efforts, it's still very difficult to control for cheating on these quizzes. Students tend to be very good at finding ways around our best obstacles.]

Saturday, August 24, 2013

What I Learned about Teaching from River Tubing

|

| View from Observation Point on the East Rim |

Part of my preparation for a new academic year involves an annual August pilgrimage to Utah, where several of my family members reside and where I can indulge my love of all things outdoors. I always spend a few days hiking in Zion National Park, including The Narrows hike back in the Virgin River (a hike that was especially awesome this year because the river was running lower and slower than usual and so we were able to go back for several miles before it became pretty challenging). The spectacular majesty of Zion, the fact that so much remains the same yet it is ever evolving, provide a great background for re-centering myself and preparing for the inevitable insanity of a new academic year. It's also nice to get out in the fresh air and enjoy some spectacular views.

This year, my mom proposed a family river trip that would include the two of us, my sister, brother-in-law, and their two children (12 and 15). We've done several of these in the past and it sounded like fun. I agreed and left the arrangements up to my mom and sister. A few days before the "river trip" I found out that it was, in fact, not a rafting trip but a tubing trip; and that it was going to be unguided. I was a little nervous about this. We were going to be tubing an unfamiliar river; none of us had gone tubing in a very long time; and our group had both young people and an older person. The company that ran the trips had a short video on their website showing happy people tubing; they also included a warning that "This isn't the Lazy River at the Waterpark." No other instructions or words of warning.

We met the company van in Park City. Our group ended up being my family and another young married couple. As we drove to the drop off point, the driver was completely silent. Upon arrival, we were all handed a tube and a life jacket. He suggested in an off-hand way that we might want to leave any valuable behind in the van. At the last minute, I decided to leave my phone. None of the instructions had suggested water shoes and most people were wearing flip flops. My mom had real water shoes and my shoes were somewhere between water shoes and flip flops. The driver suggested that people might want to leave their shoes and all the flip-flop wearers did so (to their everlasting regret).

We met the company van in Park City. Our group ended up being my family and another young married couple. As we drove to the drop off point, the driver was completely silent. Upon arrival, we were all handed a tube and a life jacket. He suggested in an off-hand way that we might want to leave any valuable behind in the van. At the last minute, I decided to leave my phone. None of the instructions had suggested water shoes and most people were wearing flip flops. My mom had real water shoes and my shoes were somewhere between water shoes and flip flops. The driver suggested that people might want to leave their shoes and all the flip-flop wearers did so (to their everlasting regret).Before he sent us down the river, the driver spent about 3 minutes giving a rapid-fire lecture on how to navigate the different parts of the river and rapids. Unfortunately, none of us could follow or even remember much past the first obstacle since a. he was speaking so quickly; and b. we had no pre-existing map to connect his descriptions to. As I looked around, I could see that everyone had tuned out at about the 90 second mark. Oddly, we were given no instructions on how to manage if we lost our tube (beyond "be sure you get your tube back"). For instance, the standard advice is to float on your back with your feet pointing downstream to protect your head from being slammed into boulders. We were given no tips for getting into our tubes; we were not instructed on technique for paddling/steering the tube nor were we warned that we would be doing a lot of this. We were told nothing about how the river was running (pretty fast, with a very complex current that required a lot of active paddling). Helmets probably would have been useful. Instead, the driver sent us off and told us he'd see us at the bottom in a few hours.

Within five minutes of setting off down the river, we came up to the first set of rapids. The current was fast and pulled us towards an area where, if we tried to go down that way, our tube would get stuck and we would flip out and get sucked down into the rapid. The only way to avoid this outcome was to know that this was coming and start paddling away from it as soon as possible. Unfortunately, because none of us had any experience on this river; and our driver had done little to prepare us for what we would encounter, the first few people ended up getting flipped (including me and my mom). Without a tube and sucked into a swift current, I instinctively turned on my back and looked for a place where I could stop and find a way to get a tube. I also needed to help my almost-70 year old mom, who had lost her glasses. The scene at the bottom of the rapid was total chaos, with people struggling to get their balance, find tubes, get back into them, etc. I had to float without a tube for about ten minutes, ricocheting from boulder to boulder and getting scratched up by the bushes and trees along the banks. Fun times.

This scene repeated itself frequently as we made our way down the river. It was always the same story: a rapid that needed to be navigated in a particular way in order to emerge unscathed; yet these rapids appeared suddenly and it was very challenging to figure out what to do--and have the time to do it--before the current took hold of the tube and dragged us down the wrong way. I had expected a calm, two hour floating trip. Instead, after the first 20 minutes, I was just hoping we'd all get to the bottom in one piece. It was especially nerve-wracking because our group had my young (and small) nephew and older mom. It was certainly an opportunity for family bonding, but not quite the kind that my mom imagined.

Fortunately, there were a few calmer stretches. During one of these, while firmly settled in my tube, I found myself thinking about how crazy it was that this driver just sent us off with little more than a life jacket and a tube. We were left to catapult down this river, fingers crossed that everyone made it to the bottom without major injuries. All of us were shocked at what was happening. We'd all taken river rafting trips where we were lectured intensively about what to do if we ended up in the water; where we were warned (excessively) about the dangers we were undertaking. Yet, in this case, where there were real dangers, we hadn't been warned at all! Every time I ended up going down a rapid the wrong way, I would realize this was going to happen--but too late to do anything about it. I found myself thinking that it would have been extremely helpful for the company to put some signs in the river banks with errors, signaling an approaching rapid and which way we should be padding to avoid disaster. Instead, we were left completely on our own--and at several points during the two hour trip, all of us ended up in the river, slamming into boulders, cutting our feet on rocks, getting scratches and scrapes from the trees on the banks.

As I was struggling to make it down this river in one piece, it occurred to me that this experience offered some great insights for teachers. As I told my mom at the bottom, my class is NOT an unguided tubing trip! That is to say, the pedagogical analog of this trip is the professor who walks into class, hands out a bare bones syllabus with a list of reading assignments and test dates, and then starts to lecture. There is no attention to the fact that many of the students won't have experience with the subject matter, won't intuitively know how to learn the material. It's the Darwinian "sink or swim" approach to teaching. In that situation, the student only figures out what they should have done after the fact, when it's too late and they have lost their tube and are slamming into boulders. No matter how hard they try to paddle away from obstacles, they find themselves getting smacked in the face with unforgiving tree branches. It's a horrible, frustrating experience.

I have changed my tune on a number of things about teaching, perhaps most importantly the role of formative assessment vs summative assessment. But another big change is my attitude towards structure (or what some might see as "hand-holding). What I am finding is that many of my students will make good learning choices if given the opportunity; but that many of them--like me on this tubing trip--don't have the experience or content knowledge to know what those choices should be unless they get some guidance from me. I had about 20% more students earn some form of an A in my blended class in Spring 2013 than in previous semesters. In large part, this was because the path away from the rapids was much more clear to more of them than usual. They were better able to see those rapids in advance and put their backs into steering away from them. This is a really important point, I think. It's not hand-holding to do a better job of helping our students see and understand exactly what is required to avoid getting flipped out of their tubes and slammed into rocks. Sometimes, without this help, they underestimate the effort that is required to avoid the shoals.

As the first day of my Rome 3.0 class rapidly approaches, I am thinking a lot about what I am going to say. I am also putting a lot of energy into carefully planning the students' orientation to the class and the different parts of it. I roll out these different parts (watching Echo360 videos, i>clickers, discussion board, practice quizzes on Blackboard, etc) slowly, one at a time. I let them get somewhat comfortable with one thing, then add another. I explain why I am using each tool and I carefully outline what my expectations are for them/what they need to do. I repeat this several times during the semester, but especially during the first month. The course is structured to take account of the fact that most of them have little experience with how to learn, engage with, and critically analyze historical narratives. I don't just throw them in the deep end and see who can swim.

We all survived the tubing trip, to the extent that we made it to the bottom alive. But every one of us had injuries. My elbows were rubbed raw from frenetic paddling and I'll likely have a scar on one forever. I was sore for days from being tossed around. My mom lost her glasses and was covered with bruises and scrapes and raw elbows. My brother-in-law lost his wedding ring and was scraped raw on his belly from saving my nephew at several points. Feet were cut and bloody from the rocks. The trip has made for some great stories, and we've all had fun texting each other pictures of our wounds (ok, my family is kind of weird!). But we all agree that we won't be doing that trip again--and that it would have been a lot better if we'd either had a guide; or the company had done a better job of preparing us and marking the course on the river.

For me, it's been a great opportunity to think about what I do as an instructor, especially in a large class; and how important it is that I sign post dangers and clearly mark the paths that will lead to a pleasant trip. Some people will ignore my warnings and hurtle over the rapids. Many, however, will make the effort to stay in calmer waters and, consequently, will reach the end of the semester having made gains in their learning; but also, having had a pleasant experience. They might even sign up for another trip.

Friday, August 2, 2013

Managing Class Meetings in the Flipped Classroom

One year after redesigning my Intro to Ancient Rome class, I feel like my world has been turned upside down. In many ways, it has. I approach teaching in an entirely different--and far more thoughtful and informed--way; and I am more committed than ever to being an advocate for experimentation with the techniques of blended learning. There's no single right model for "flipping" or "blending" a class (nor is there even agreement among learning theorists about what, exactly, these terms mean). In its most successful format, my large enrollment course is probably best described as a modified flipped class. I still do some lecture during class time, about 20 minutes or so; but use most of class time to review and practice difficult concepts; work with students to make connections between different parts of the course; and ask students to engage critically with the complexities of Roman history.

This past year has been enormously challenging, emotionally and physically. Undertaking a project like this is not for the faint of heart. Had I fully grasped what I was in for, I never would have done it. Seriously. When I encountered pretty significant student resistance to the flipped model in the fall semester, I toyed with the idea of giving up. For better or worse, though, I am one of those people who hates to fail. I really, really hate it. I was also very lucky to have the support of an amazing group of people affiliated with UT's Center for Teaching and Learning, especially Stephanie Corliss, Erin Reilly, and Julie Schell. I'd be lying if I said that I enjoyed Rome 1.0 in Fall 2012. I hated it. I was miserable, frustrated, and exhausted. I cried a lot. I adopted two adorable kittens and posted a lot of cute kitten pictures on Facebook.

But I am stubborn and I knew that I could fix at least some of the big problems: too much outside of class work; not enough structure; needed to modify the assessments to match the course design; needed to find a way to define myself somewhere between "sage on the stage" and "guide on the side". I needed to make it clear to the students that I was "doing my job", even if it looked a bit different from what they were used to in a lecture class. Any instructor knows that it is so much easier to lecture to 400 students than it is to try to run an active and engaged class. In the fall, I completely flipped the class. I did no lecture during class time and used class time to identify misconceptions, review factual material, and encourage analysis. This approach was a massive mistake in a class that had essentially no direct contact with me, not least because it left the students with the impression that it was just an online class and that class time was a "waste" because I wasn't delivering content. The low point came when some of them started a thread on the class FB page (I wasn't officially a member but I heard about it) titled "I Hate the Flipped Class."

As well, I made the mistake of retaining my old assessment structure of 3 midterms and a final. In retrospect, it was no surprise that the students refused to flip and therefore got little out of class meetings (if they even bothered to show up). They just crammed for the exams and resented having to binge view so many lectures in addition to the assigned primary and textbook readings. By about week 6 of the fall semester, I felt like I was the ringmaster of a circus, desperately trying to keep all the lions and tigers from attacking me and running loose. It was not a fun teaching experience, but I learned a lot from the failures.

Going into the fall semester, I assumed that the most challenging piece would be mastering new classroom technology, particularly the i>clicker. Certainly, it took some time for me to figure out how best to integrate i>clicker questions, how to find a balance between spot-checking factual knowledge, using them to teach new facts, and seeking opinions (and, again, all the research and advice I found on this topic was essentially useless because it was aimed at problem-based disciplines, not humanities). I also use a fair amount of peer discussion. It's a huge, awkward classroom with fixed seating so I used the "turn to your neighbor" technique. Again, it took awhile to figure out how to use peer discussion effectively. The most important lesson: keep it short and sweet. It's better to stop them mid-sentence than have them talking about their weekend plans. I usually had them discuss something for 60-75 seconds. Eventually, I got pretty good at moving between peer discussion, i>clicker polls, and group discussion, depending on the issue. I frequently improvised. So, for instance, I might start with an i>clicker poll and, if there was a lot of divergence, I'd have them talk to their neighbor and then vote again. Or, if they got the question right, I might follow up with a tougher question and have them discuss it with their neighbor and then we'd discuss it as a class.

When I got this right, it was a lot like a well-choreographed dance. I tried to speak no more than 2-3 minutes before asking some question that required them to click in, talk to their neighbor, etc. When we did ethics case studies, they had in class worksheets to fill out. For some of the questions, I asked them to work on their own and then compare answers with a peer; for others, we'd discuss it as a group. In the spring semester, the students took a short (10 minute) quiz at the start of class every Tuesday. I did these the old-fashioned way, with scantron forms and a timed Powerpoint. Once we got the system down, it was pretty seamless. The quizzes covered the material from the previous week as well as the readings/viewings due on that day. This meant that I could assume a high level of preparation on Tuesdays and thus rely a lot on peer discussion to do higher order analysis of the content. The key, I found, was to introduce a lot of variation in classroom activities and keep things moving. The bigger the class, the faster things need to move, I think. As well, my goal was always to keep as many students as possible engaged at any single moment--so I avoided too much student-instructor discussion. Finally, I gave them candy if they contributed to class discussion, a tactic that was extremely successful in eliciting contributions from around the classroom!

A big lesson, and something that I wasn't at all prepared for in the fall, was the fact that I would have to relearn from scratch how to teach a large class. I was very comfortable and good at teaching lecture classes, but this was an entirely new experience. Proponents of the flipped class like to describe this transition as moving from "sage on the stage" to "guide on the side." That's not at all how it worked for me. When I tried to become a "guide", students revolted. They thought I wasn't doing my job; they assumed I didn't know *how* to do my job. I've never experienced such openly disrespectful behavior in a classroom as I did in Fall 2012. I realized that, in a large enrollment class, the only way I really had to construct my authority as the expert (and to remind students of that authority) was to perform the role--that is, to be an occasional sage on the stage. The trick was to find a way to balance these different roles, it wasn't to exchange one role for the other--at least not in a large enrollment class and not for me (I'm female, 5'3 and look like I am maybe 30).

Once I figured out my role in this new classroom environment, things went much more smoothly. I was still asking students to play somewhat different roles than what they were accustomed to, but it worked once they saw that I was comfortable and confident in my new role. To my mind, the biggest challenge in a flipped class is this redefinition of roles. It is going to vary a lot, from instructor to instructor and class to class. As instructors, we are accustomed to developing a consistent teaching persona. The flipped class, which shifts the focus from the instructor to students, demands that we always be ready to adapt. Teaching becomes much more improvisational (and therefore nerve-wracking). It requires a lot of thinking on one's feet and a willingness to go off script at some point (often multiple points) in every class--all while making sure that the day's material is covered. To give an example: about 30 minutes before every class, I would get the viewing stats for the assigned lecture(s). If about 2/3 had viewed the lecture, I knew we'd have a smooth day; if 50%, I knew there'd be places where I'd have to do a bit more content delivery than planned; if lower than 50%, I'd have to revise some of the discussion questions and rely less on peer discussion. I could have a great plan in place, but the success of it always depended on the students--and on my ability to quickly improvise if the students had not prepared or, for some reason, misunderstood a concept that I assumed would be basic.

The basic goal of a flipped class is to make learning more efficient for students. The challenge is that they are so accustomed to learning in other ways that they tend to resist taking on the role of the "flipped class student". I learned the hard way that trying to reason with them was pointless. As a group, they simply could not see that the class activities were designed specifically to help them learn how to learn Roman history. They were convinced that they already knew how to learn and that I was an obstacle. In the spring, I made a point of not referring to the class as flipped. I just explained how the class was going to work; what was expected of them; and used the phrase "active learning" ad nauseam. I also introduced an enormous amount of structure and made sure that every activity was incentivized, so that they would be able to see for themselves how each activity was helping them to learn. Finally, I introduced exam wrappers as a way of encouraging them to reflect on their learning strategies and better understand how the different parts of the class were contributing to their learning. One of the more interesting things: attendance was very strong (about 300 on Tuesdays and 250-275 on Thursdays) although every class was captured and there was no attendance requirement. These numbers remained consistent throughout the semester. A large number of students clearly figured out that the in class work activities were an efficiency, were saving them study time down the line. It was fascinating to see them discover this for themselves and then adapt their behavior.

If anyone is interested in seeing a PPT from one of my classes, I'm happy to share. I'm trying to get one of the class sessions made available for public viewing (but we'll see). The bottom line: I don't think it matters much exactly what you do during class time. It definitely doesn't need to be high-tech, bells and whistles. It's more about a. developing a clear understanding of your changed role in this environment, while being sure that it's clear to the students that you are still running the show and communicating to them your expectations for them; b. designing activities that force individual students to be involved at all times, as much as possible; c. paying attention to variety and pace; and d. being comfortable with improvisation. It's a requirement in a student-centered classroom. I constantly reminded myself that it was about my students, not me. It was my job to meet them where they were and find ways to get them where I needed them to be by the end of a given class period. Sometimes class played out exactly as I had planned. Most of the time, it did not. At the same time, as I grew more experienced in my role, I became a lot more skilled at using things like i>clicker or discussion questions rather than lecture to teach.

It is enormously challenging to run a flipped classroom, especially when dealing with hundreds of students and inadequate instructional support (I had one TA/100 students). It is stressful and sometimes frustrating and depressing. It takes a lot of trial and error, and a lot of tolerance for failure and resilience to student guff (surprise! some students love lecture! not all students are desperate for active engagement!). It is also tremendously rewarding to see students learning deeply and well, to see them making connections and raising insightful questions. It was a very hard year for me, but deeply satisfying and exciting. I'm very much looking forward to the start of Rome 3.0 in a few weeks!

Thursday, August 1, 2013

Some Responses to Questions in the Comments of "Intro to Rome": The Flipped Version

Last week, I published a short overview of my experience with flipping (or blending) my 400-student Intro to Ancient Rome course in the Chronicle of Higher Education. Space was limited and a lot of important details had to be cut. As well, the day after the article appeared, I immediately became extremely ill and so was unable to participate in the wonderful discussion that followed the article. I was overjoyed to see that it elicited so many thoughtful comments and questions. I certainly don't expect that everyone will be a fan of the flipped class approach, or believe that it truly can improve student engagement and learning. That's ok. My aim in writing the article was to give a first-person account of the experience, warts and all; and to offer some thoughts on how the dynamics of a flipped classroom might not be well-suited to relying on content delivery by someone other than the course instructor. I am a big supporter of MOOC instructors using their own content to flip their own classes, as Duke Biology professor Mohamed Noor has done so successfully.

I am going to be continuing to work on and assess the effectiveness of my large enrollment Intro to Rome course with a team of learning specialists; and, in the coming semesters, we'll be experimenting a bit with different modes of delivery as we try to identify the types of students who thrive in different environments (small seminar, large enrollment lecture, blended large enrollment lecture, non-MOOC online). Our goal is to be able to deliver this core curriculum course on a range of "platforms" and to support both synchronous and asynchronous learning. I'm very excited about the project and have been delighted that the course has received funding support from both the Course Transformation Program at UT Austin (for the classroom-based, blended version); and from the UT System's Institute for Transformational Learning (for the online version). I am also hoping that the project will become one of the inaugural research projects for a new teaching initiative sponsored by the Provost's office. Fingers crossed!

I did want to answer some of the specific questions that were raised in the comments on the article or in conversation with me via Facebook and Twitter. A common concern that many people have is "Why flip a class?" This is a very good question, especially in reference to a large enrollment course taught in an auditorium. The space of the room, as well as the number of students, makes any kind of peer-to-peer interaction during class time exceptionally difficult and difficult for the instructional team to manage. In my case, I had never heard of the flipped class or blended learning when I approached our IT Department in early Spring 2012 about the possibility of pre-recording my class lectures. My motives were most decidedly not to experiment with the shiny new pedagogical theory--I was too clueless to even realize that what I wanted to do was something called "flipping the class."

I had taught the course in Fall 2011 as a lecture course, but was in a room equipped with Echo360 lecture capture. I quickly realized that, with the lecture capture technology, I needed to rethink what I was doing during class. Coincidentally, I was approached by a friend in our College of Undergraduate Studies about adding an "Ethics Flag" to my class. They were looking to convert a few large enrollment classes to" Ethics-Flagged" courses and mine seemed like a good possibility--after all, the Romans engaged in a lot of ethically questionable activities! I knew that if I was going to add the Ethics component to the course I was going to need to, first, shift some of the Roman history content out of class; and second, find ways to make the in class experience more active and engaged. This was the impetus to do what I later learned was "flipping the class". As I learned more about the flipped class model, I was also intrigued by the promise of learning gains. I wasn't sure how the research on small flipped classes would translate to a large enrollment flipped class, but I was curious to see. Before I flipped the Rome class, I struggled with being unable to expect students to do more than regurgitate factual information on exams. Any time I tried to push them to do more interpretive work, the results were disappointing. I felt like I couldn't expect them to improve unless we were practicing those skills in class, yet the logistics of a large class with 1 TA/100 students made any kind of sustained practice with regular feedback nearly impossible.

One of the reasons I had never heard of the flipped class model is that, as a humanist, all of our small courses are theoretically flipped. This is certainly the case when I teach an upper division Latin literature course (in Latin). I assign the students to read Latin and perhaps also some secondary literature. We review problem areas and do application exercises during class time. For humanists, there's nothing particularly innovative about flipping a class. What is innovative about my project is flipping a large enrollment course. Even if some faculty will say that, in a 400 student class, they assign readings and then "discuss" them during class, the reality is that faculty are largely founts of information, delivering content while students scribble notes. Sure, a few students will chime in from time to time, but with very few exceptions, these courses are lecture courses. As well, I think there's something important about being deliberate about one's pedagogy (an excellent post by Robert Talbert expanding on this point). After my experience with the Rome class, I've been much more deliberate about protecting class time for learning activities that require my presence even in my small graduate seminars. As a result, students are taking a much more active role in the classes and there is a much stronger emphasis on peer instruction. Sure, these seminars had always had these elements in place; but now they are there in a deliberate and thoughtful way, and I regularly ask the students to reflect on how they are learning.

One concern that is regularly raised when I talk about my flipped class is the issue of overloading students with homework. This is a valid and serious issue. I screwed it up when I did the first version of the flipped class--there was far too much outside of class work and many students let me know that on the end of semester surveys. They were right. When I reworked the class for the following semester, I deliberately cut the homework back. This meant bringing back some content delivery to class (which was a good idea for other reasons as well). It also meant cutting out some of the content. In the non-ethics flagged, lecture course, we went all the way to the fall of the western empire in 476 AD. In the Spring 2013 ethics-flagged version, we stopped with the death of Marcus Aurelius. As a specialist of the 3rd and 4th century AD, I was disappointed to cut this part of the course out but it was clearly necessary. I was then able to spread the assigned textbook readings out a bit more, as well as the assigned lectures. I cut the number of assigned lectures from about 50 to about 25. I did add a few short primary readings for the ethics cases, but none that were more than a few pages. Students still found the class to have a lot of reading, but that was more reflective of their non-liberal arts background than any excessive assignments. I feel like the current version gets it right, but it definitely took some tinkering and a reality check. I also learned that I had to put in place weekly quizzes to motivate them to keep up on the assigned work. This also worked extremely well. Without this enforced pacing, it would have been very easy for students to feel overwhelmed with all the course materials: textbook readings, pre-recorded lectures, recorded lectures, practice questions, etc.

The other common question: so what do you do in class in place of lecturing? That's a question that deserves its own post...

Wednesday, July 31, 2013

Exam Wrappers

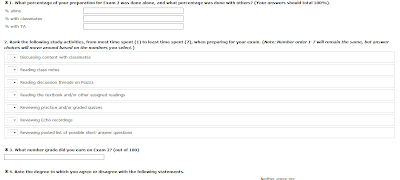

One of the most significant additions to my Spring 2013 flipped class was exam wrappers. These were relatively short surveys, posted on Survey Monkey, with questions designed to induce the students to review their exams; reflect on their preparations and study strategies; and think about how they might address any deficiencies in their performance. They were also intended to encourage students to recognize the role that some of the graded and ungraded formative assessments played in preparing them for the exam.

We returned the graded exams one week after they were taken and posted the exam wrapper. Students had a week to do the exam wrapper and received 2 extra credit points on the subsequent exam. As well, if they did ALL of the surveys during the semester (there were a lot since we were trying to learn as much as possible about their learning), they received two points added to their final grade.

The exam wrapper for Midterm #2 can be found here (just enter random numbers for the ID info and click next to see the questions; here are some other examples on the Carnegie Mellon Eberly Center site). These were created by an assessment specialist at UT Austin's Center for Teaching and Learning, Dr. Stephanie Corliss. I reviewed them and made small suggestions. The point of the exercise was a. to encourage students to pick up their exam and look at it; b. to have to spend even five minutes thinking about how they studied and, hopefully, recognize for themselves what strategies worked and didn't work; and c. to remind them of all the different learning tools available to them to prepare for the exam (practice quiz questions, recorded lectures, etc.)

What most surprised me about the exam wrappers was the extent to which they did my job for me, but far more effectively. Normally, I would offer a short review of the class performance on the exam and then talk about common problems. As well, with each exam, I would point out to them ahead of time ways that the content might post particular challenges or require particular approaches to mastery. Between the weekly quizzes and the exam wrappers, however, I found that the students were largely able to self-regulate and self-correct. Semester after semester, I have told classes that cramming for my exams is not a particularly effective strategy, particularly for exams 2 and 3. This went in one ear and out the other. But when these students saw these difficulties crop up in small doses on their weekly quizzes, they adjusted on their own. Likewise, when I read through their comments on the exam wrappers, it was absolutely clear that they had identified the sources of trouble for themselves. Sometimes it was too little preparation; more often, though, they had important insights into how their preparation strategies were wrongheaded; and a clear and effective plan for adjusting them.

I have also used exam wrappers in graduate seminars to extremely good effect, particularly in a class that focuses on improving students' abilities to read large amounts of Latin quickly. They instill in students a habit of self-reflection and self-regulation. They encourage students to see midterm exams (or quizzes) as formative assessments, as offering feedback on their learning strategies. Most importantly, they remind students of the resources available to them to learn the course material; and emphasize that there is still time to make adjustments and improve their performance. I expected my graduate students to become more reflective learners. I was, quite frankly, very surprised to see how effective the exam wrappers--together with the weekly quizzes--were at helping my undergraduates to reflect on their learning strategies and make appropriate adjustments. These adjustments were clear in their grades, as they improved even as the difficulty level of the course increased.

Tuesday, June 18, 2013

A Response to Anant Agarwal's Call for Teachers to Join the Revolution

This past weekend Anant Agarwal, the president of edX, published an op-ed in The Observer titled "Online Universities: it's time for teachers to join the revolution." There is much in his rather self-serving op-ed to criticize (and parody, as Jonathan Rhees has done so brilliantly), but perhaps the most important thing to point out is the false premise of his title. Current teachers are cast as Luddite resisters who have dug in their heels and are opposing something that is improving education. This is a complete misrepresentation of practicing educators at all levels, many of whom regularly use a range of education technologies as well as tried and true pedagogical methods to produce learning in their students. In fact, education technology has been a presence in K-12 as well as post-secondary classrooms for at least a decade, and has expanded tremendously, especially on college campuses, thanks to the availability of fast broadband connections.

To suggest that the pre-MOOC university professor was teaching with chalk and yellowed notes is an absurd caricature whose sole purpose is to position MOOCs as the shiny new thing that will revolutionize education. Agarwal declares that the "days of the old ways of teaching are numbered". While there are certainly examples of "the old way of teaching" on every college campus, I suspect that they are vastly outnumbered by the many innovative, technologically savvy, and dedicated faculty who are working every day to improve student learning.

MOOC supporters repeatedly point out that the platforms and price point (free) improves accessibility. I will leave it to others to explicate why this isn't quite true (and here). Certainly, by putting courses on an open access platform, their is the potential to improve access. But it is far from clear that MOOCs really are doing much beyond making lifelong learning more convenient; and targeting gifted learners in third world countries.

The most significant source of my irritation with the self-promoting MOOC rhetoric is centered on the claims that the mode improves learning--and, specifically, that it can support better learning than can a campus-based, large enrollment course. In basic terms, there's no evidence to support this claim, at least not yet. Furthermore, given the demographics of current MOOC users, it seems to me unlikely that even extensive study of data from individual courses or users is going to be generalizable beyond a particular course or a small subset of users. This is a big claim to make, and it requires clear data, not anecdote and declarations.

Working teachers need to know how particular students at particular universities in particular courses learn. Much more useful would be funding projects to study currently enrolled students, especially a public universities. As well, we need to know how best to help our beginning students learn HOW to learn, especially how to learn in a post-secondary setting where instructors aren't teaching to tests. Since the majority of current MOOCs users are degree holders and experienced learners--that is, they are people who already know how to navigate a course, study, be self-motivated, etc--the data being collected is unlikely to yield much of value. This will change as more of the students are actual college students with all the complexities that college students present, when the data sets can be narrowed down to "current UT students taking X course" but that is years in the future. As Rob Reich explains, "If MOOCs promise to enhance student learning, they must show that they deliver at least as powerful outcomes as traditional lecture classes in universities and community colleges. If not, their virtue is their democratizing potential; but they will only be better than nothing."